Hi there! This blog is no longer maintained. All posts here have been migrated to my main blog, sarriest.wordpress.com.

Your team has had a successful brainstorming session (or sessions), and now you guys have a ton of ideas. Now what? How do you narrow it down? This might seem like a daunting task, especially for larger projects which have a hundred or more ideas. A Google search will turn up millions of suggestions, but for this post, I’ll be focusing specifically on narrowing down your ideas for a transformational game. Why transformational games? Because that’s what my team is currently working on (more on that later). The general process for narrowing down your ideas isn’t sufficient, and there is woefully little relevant material about this on Google.

Transformational games are developed with the intention to create a real world change in the player which persists outside of the game, be it in the form of knowledge, belief, behavior, etc. It’s an umbrella term which encompasses other categories, like educational games, training simulators, games for health, and so on. The two key ideas here are transfer (the change extends to the real world) and persistence (the change remains after the game is over).

My group has the interesting challenge of creating a live transformational game for our client, Games for Change (G4C), which will be played during their NYC festival in June. We were given the topic of gun violence in America, and have since narrowed it down to gun ownership and gun control. As you can imagine, this is one of the hottest and most controversial topics here, which all too often degenerates into name calling and finger pointing. No surprise why the faculty say ours is the hardest project this semester.

This year’s G4C Festival, at which we’ll be running our game.

We started with research, followed by brainstorming. Since none of us are Americans, we had the advantage of being able to see this issue from a more objective point of view, instead of being overly attached to it. By the end of our multi-day brainstorming process, we had over 30 high level ideas, with a number of them having more details. As with other G4C teams in the past, choosing an idea to work on was one of the biggest challenges of our pre-production stage. We needed some form of criteria, but how do we set a criteria if we don’t even know if any of the game ideas can affect a change in the player?

Fast forward to quarter presentations. During the sitdowns, one of the faculty, Jessica Hammer, came to our rescue. Jess Hammer has been researching and designing transformational games for years, and gave us an incredible amount of insight for our project. She taught us a framework and process for narrowing down ideas for transformational games, which is what I’ll be sharing here.

The framework

For each idea we had, we were to distill them down into three main sections: What, How, and Design. What: this is the actual change we want to affect in the player. How: what strategy are we using to affect this change? Design: how does the game mechanics support our strategy? Sounds simple, right? Wrong. I’ll illustrate what I mean based on one of our ideas which Jess walked us through.

In Faction Wars, people play as characters in different factions, choosing if they wanted to own a gun or not, given their group’s motivations. For example, group A are the gangsters, who want guns to protect their territory. Group B are normal citizens, who want guns to protect themselves from the bad guys. Group C is the police, who want guns to protect everybody else.

These arbitrary factions all have valid reasons for owning a gun, especially since the goal is to survive till the end of the game. And survival games have all taught us that you need a weapon if you want to do any surviving. The twist here is that everybody dies in the end, because of regular game events which kill a certain number of people based on how many guns there are.

It’s simplistic, yes, but remember, this is just the high level concept. Now, based on this description, try coming up with the What, How, and Design. I’ll share how Jess did this below.

.

.

.

.

.

Finding it difficult? We did, too.

.

.

.

.

.

Here’s the answer:

What: Disrupt the idea that guns = defense

How: Satire

Design: Prisoner’s Dilemma

Wait, what?? How did Jess come up with this?! Time for a step by step walkthrough.

Ultimately, the real world change of Faction Wars is to get people to choose not to own guns. But that’s a bit broad for this, so we need to dig deeper – what exactly changes in their mind that would make people choose not to own guns? Back to the game, the only way to win it is if everybody chooses not to own a gun. The motivation for each of the factions boils down to them wanting to protect themselves, and without a gun, they cannot do that. Or so they think. At this point, it becomes clear that we want to bring about a change in people’s belief that owning a gun does not mean you can protect yourself or the people you care about.

The How is more tricky, and is not to be mixed up with the Design. This is the overarching strategy which you’ll be using to deliver your game. In the case of Faction Wars, there is irony in the fact that the more people whose characters own a gun for protection, the greater the probability of all of them dying. Satire, basically.

As for the Design, this is sort of like giving an overview of what the players will be experiencing in the game. To win Faction Wars, the players all need to choose, separately, not to own a gun. But why would any rational person choose that option, if that means taking the risk of being the only (or one of the few) gun-less person in the game, and putting yourself at the mercy of the bad guys? Society might be safer as a whole, but so what! I want my character to survive! If you think about it, this is exactly what the Prisoner’s Dilemma is about.

The process

Once all the ideas are in the above format, we need to ask ourselves the following questions:

-

Is the What for your idea really valuable?

-

Does the How lead to the What?

-

Does the Design lead to the How?

-

Does the game have transfer?

One. Using Faction Wars as the example, its intended change is definitely valuable, because guns = defense is a problematic belief. Owning a gun might make you as an individual feel safer, but collectively, as a society, increases the risk of gun violence. No, this is not an assumption we made; it’s based on research.

Two. Can using satire bring about this change? Potentially, because the irony and exaggerated consequence of everybody dying in the end does help to expose the problems with this belief.

Three. Will using the Prisoner’s Dilemma as a mechanic help with our chosen strategy? Yup. Assuming the players are rational people who want to win the game, it is likely that on their first playthrough, most people will choose to own a gun given the motivation and background story/info the game provides. This automatically sets the game up for failure, which is when the game’s satirical nature shines through.

Four. What about the transfer of change to the real world? The game leads the player to deduce that their character owning a gun might not mean it can defend itself. This in-game conclusion is similar enough to the real world change we are after that the game stands a pretty decent chance.

If the game idea gets a solid yes for all four questions, then good for you! If the idea has a couple of maybes, then it needs some more thought, and goes into the idea iteration pile. If you get lots of nos, you probably don’t want to use that idea. Note though, that sometimes just refining the What, How, and Design while keeping the idea the same can change a no to a yes.

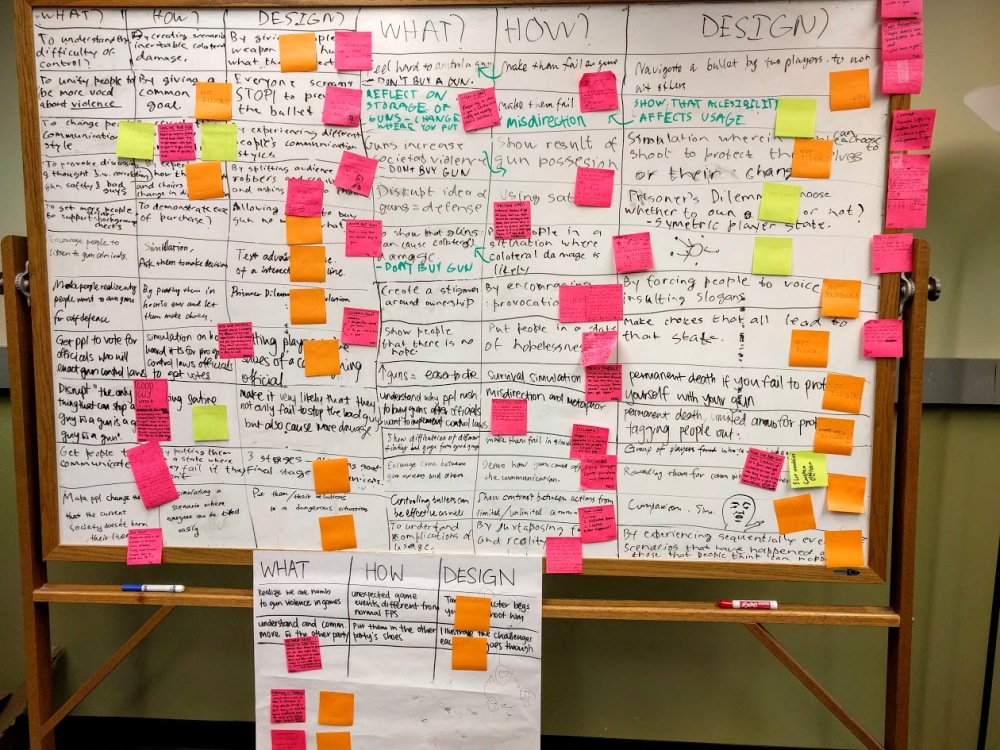

At this stage, you should have at least 3-5 ideas which passed the above criteria. Any less means your original pool of ideas was too small, and it is recommended to go back to brainstorming. Our group ended up with six ideas and a hugely messy, yet satisfying, whiteboard.

Narrowing down our ideas. Pink = idea description, orange = fail, yellow = pass.

With the narrowed down ideas comes the opportunity for anybody in the group to veto an idea, without needing to give a reason. This last part is important, and you should only veto something if you really dread working on it / believe it’s not possible to implement given the constraints of your resources (let’s fly to the moon!). Not really liking that idea / wanting your idea to be chosen instead are invalid reasons. This requires trust in your team members, because whether they want to share their reasons for vetoing an idea is completely up to them. My team didn’t veto any ideas.

Lastly, from the remaining ideas, just pick a few to prototype! At this point, it really doesn’t matter which idea you pick, as all are above bar ideas. If one idea somehow doesn’t work, there are still others to fall back on. My team was really excited about one idea in particular (see the idea with two yellow stickys?), so we decided to go with that.

And that’s it! Hope this helps (:

P.S. if you’re wondering what my stand on this issue is: I think all guns should be banned. Why? Because I’m Singaporean and I think everything which causes problems should be banned, like chewing gum 😉

Man! That was one hell of a brainstorm 😛 Jessica Hammer can just dive straight into the essence of the problem and solve it for you in an instant. She had helped us with our process as well. She’s just wonderful. Also, during the research, did you guys ever come across the use of guns for hunting or using it in places like shooting ranges. Just curious. I also liked how you used the prisoner’s dilemma problem from game theory to break down the issue.

LikeLike

Using the prisoner’s dilemma to make a game about gun violence is a cool idea. I also found the part of your process about vetoing ideas really interesting, especially since you don’t have to give a reason to veto an idea.

One thing that I’m wondering is how you would test your game. Unlike normal playtesting, where you iterate on the experience of playing the game, you’d also need to iterate how effective the “transformational” part of your game is. This seems like something that is really difficult, especially with a topic like gun violence.

LikeLike